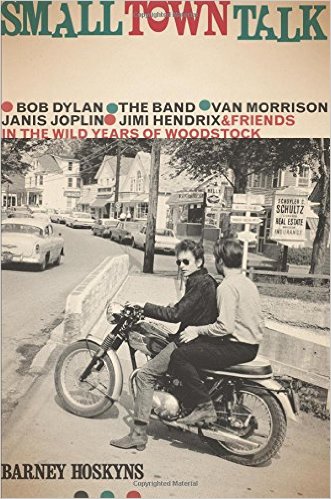

In the small town of Woodstock we meet a fresh faced Dylan, Janis, and Jimi on their way to the top, but reviewer Joe Gallo cautions against judging this book by its cover.

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns

Bo Diddley, guitarist, songwriter, and literary critic, once said, “You can’t judge a book by looking at the cover.” But I do it all the time. In fact, I liked Barney Hoskyns’ book, “Small Town Talk”, before I even started reading it. My first thought looking at the cover was, “I never saw that picture of Dylan before…” He’s on his motorcycle, idling at a cross street looking cool as death. Classic Dylan: ‘65 or ’66. Here’s the guy who went electric, the guy who puzzled the waking world with his surreal poetics, cryptic stances, and underground mystique. According to the subtitle, this book was going to be a wild ride through the Woodstock of Dylan, The Band, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Van Morrison and friends. If the book lived up to it’s cover, this was going to be one hell of a ride.

As it is written in the Book of Hoskyns, we first see Woodstock (the book’s main character), as a working class farm town. That was before the first wave of Bohemians came to stay in the early years of the 20th century. The balance between the conservative worker bees and the free-floating and (sometime) freeloading Bohos was always a precarious one. Basically, it came down to numbers; the Bohemians were outnumbered and although they added to the local economy, they weren’t its driving force. This scenario would change with the arrival of Mr. Albert Grossman, maverick manager of such legendary folkies as Peter, Paul, and Mary, Odetta, Phil Ochs, Richie Havens, and his young cash cow, Bob Dylan.

Much of the book is taken up with Grossman. Grossman the maverick, the genius negotiator, the cruel manipulator, the father figure, the generous gourmand, and the cunning, calculating bastard of commerce… Here’s a guy who pretty much adopted Dylan, persuaded him to move to Woodstock, nurtured his career, fed his paranoia, and stoked his pride with unimaginable riches. This is a guy who knew where the money was, and offered his 21-year old charge a contract that guaranteed that Grossman, the manager, ended up with 50% of Dylan’s publishing rights. Years later, when Dylan threatened litigation, Grossman’s summation was basically, “who the hell signs a contract without reading it first?” Legally, Grossman was right, but morally it was a pretty crappy thing to do to a kid.

Grossman pulled the same kind of brutish calculation on Janis Joplin. He really loved Janis and was altogether unflagging in his devotion to her and her career. But when she showed signs of self-destruction, Grossman took a $200K life insurance policy out on her. Since her death was ruled a suicide, he only cashed in on $100K of it, and that was after protracted legal wrangling.

The effect Grossman and Dylan had on Woodstock was incalculable. Dylan had big footsteps to fill, and The Band soon followed in his wake. Then came the notables and their hangers-on, the groupies and the flower children, and then came the drug dealers, junkies, frauds, and scarred-for-life failures.

Everything written about the folk heroes we know (and sometimes love) is positively compelling. In fact, Hoskyn’s depiction of Dylan’s life before, during, and after his motorcycle accident was the best summation of that period I have ever read. This includes his recovery from the neck injury (and possible withdrawal from drug addiction), his collaboration with the Band at Big Pink (the Basement Tapes), and his inner struggle with being mythologized. To facilitate the molting of the myth-man, Dylan tried to his best to become a typical family man (it didn’t work). He made great strides though. In an effort to protect his family, he bought a big ol’ rifle to keep them damn hippies off his property…

Now, here’s where the cover starts to fade on Small Town Talk.

Small towns are known for being as gossipy as Peyton Place and the small town of Woodstock is no different. Against our better angels – or in service to our more bitter ones – we all succumb to gossip, especially when it concerns our folk heroes (and to me, Dylan and Hendrix and all the rest are folk heroes). So when you overhear the good stuff, the stuff that sheds new light on their lives and music, it makes for a compelling read. But to hear gossip about people you never heard of (or heard of but don’t really care about) it’s really asking a little too much of the reader.

Once Dylan, Joplin, Van Morrison, and various members of the Band leave that bucolic, little town, the book slumbers to a snore. It pepped up a bit when Todd Rundgren came into the picture, but the remainder of the book – some 80 pages by rough calculation – is dedicated to such immortals as Geoff and Maria Mulduar, Karen Dalton, Jesse Winchester, Bobby Charles, and a host of other minor characters, few of which seem to require the space allotted to them.

By the end of the book, Albert Grossman and Levon Helm are dead, and Woodstock has devolved into a world of suicides, train wrecks, burnouts, and drug-addled has-beens. Although the famed concert never took place there, Woodstock, the town, has now become a peace and love tourist trap that was murdered long ago by the counterculture it supposedly helped bring into being. The Age of Aquarius may be dead, but it’s desiccated carcass marches on. And this, Small Town Talk illustrates with candor, sincerity, and unfortunate tedium.