In 2013, at the age of 53, musician and author Scott Miller unexpectedly took his own life, leaving behind a wife, two children and a legion of devoted fans. It was a sad end to a 30+ year career for the frontman of a pair of critically acclaimed college radio staples Game Theory and The Loud Family.

In 2013, at the age of 53, musician and author Scott Miller unexpectedly took his own life, leaving behind a wife, two children and a legion of devoted fans. It was a sad end to a 30+ year career for the frontman of a pair of critically acclaimed college radio staples Game Theory and The Loud Family.

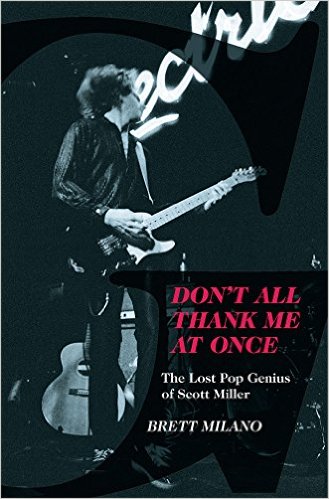

Since his passing, interest in Miller’s catalogue has intensified, meriting a spate of re-releases, a rarities album, and a new biography by (Rocker’s own) Brett Milano. We caught up with him round the water cooler to hear all about it.

_____

Rocker: What was your relationship to Scott before you wrote this book? Did you know him personally?

Brett: As you certainly know, Scott was a lovely guy and very appreciative to those who were fans of his music. As I mention in the book, I first got an early Game Theory EP and gave it a negative review in [area music magazine] Boston Rock — He never mentioned that to me but I know he asked that someone else review the follow up. Of course his music took some quantum leaps afterwards, I became a fan, interviewed him a few times and we were casually friendly. By the time I was working for Alias Records in 1992, he was sending me demos for what became “Plants & Birds & Rocks & Things”— I made it my mission to get that album released, and got thanked in nice big print on the back. The last contact I had with Scott was when I complimented him on his book (“Music: What Happened?”) and he wrote back saying it was great to hear a “real writer” praising it — Something I can’t look at for fear of getting too teary.

Rocker: How and why did you decide to write this book?

Brett: In early 2014 there was a call for proposals in the 33-1/3 series, and I decided to propose Game Theory’s “Lolita Nation.” Though it didn’t sell as well as the albums they usually choose, I thought it had enough critical rep by now that it stood a chance of being accepted. I started doing interviews, with [Game Theory record producer and Let’s Active frontman] Mitch Easter and Game Theory drummer Gil Ray, and wrote what I thought was a pretty good proposal. I did make the first cut before they turned it down, the rejection letter basically said “We can’t do it, but I love this proposal.” By that time I knew that people in Scott’s orbit were behind the idea, including Sue Trowbridge of 125 Records who said she would publish it. But I knew that I had to turn it into a proper bio and not just a pseudo-33 1/3.

Rocker: How long did it take you to complete?

Brett: About ten months, but this was a stretch that I wasn’t working full-time, so most of the creative energy I had went into the book. As a former newspaper journalist I find that giving yourself strict deadlines is the only way to get anything finished. So I put last spring as the deadline, so we could have the book out by late fall—particularly so it would coincide with Omnivore Records’ reissue of “Lolita Nation”. Turns out we beat that by about a month.

Rocker: Although you have 4 other books under your belt, this was your first biography. Were you daunted by the task initially?

Brett: Yes, plenty daunted. Probing into someone’s personal life is a lot more of a challenge than just covering music, particularly someone as private as Scott. I was helped there by his family, friends and bandmates, all of whom were still processing the loss in different ways—he’d barely been gone a year when I started work. I was knocked out by how supportive they all were, and it became clear that we had a really compelling story there. Aside from Scott being such a fascinating character, Game Theory in particular was so full of colorful personalities. There’s a lot of musical detail in there, but telling the personal stories was more challenging and more rewarding.

Rocker: Were there preconceived notions you went in with about Scott and his life that changed by the time you were done?

Brett: I think some people had the idea that he was chronically depressed, which for most of his life wasn’t true. A lot of our preconceptions about him were accurate though—He really was a Vulcan type who kept his emotions under wraps, didn’t do much drinking or drugging, didn’t mess around on the road. The fact that he got so much into being a dad was news to me though—He certainly wasn’t sitting there sulking for the ten years after he stopped doing music. The notion of his eating his daughters’ shaving-cream pies was a new one on me. And of course, it makes the end of the story make even less sense.

One surprising thing I did learn was that Scott took a spiritual turn later in his life, becoming fascinated with Rene Girard in particular. Yet he embraced a very earthly kind of spirituality, less about the afterlife than the importance of being a good person in this world. As people know, there was some deep despair in his songs but that’s hardly all there was, and at least one band member warned against trying to draw too many conclusions based on his lyrics.

Rocker: Your book is really one of the first places it’s told definitively that Miller took his own life, but you shy from telling the details of his death. Why did you elect to go that route?

Brett: That would be the proverbial elephant. I think Scott’s fans respected the boundaries of his wife and family, which is why such things were never discussed online. But I think everyone understood that if I was writing a biography, the fact of his taking his own life would need to be addressed. In terms of how he actually went about it, that’s information that the family hasn’t made public, and I chose to respect that—His wife Kristine was otherwise extremely generous with her reflections, and I was more concerned with trying to get into his mindset in his last couple of years. So I tried to hold the line of not being exploitive without shirking my responsibilities as a biographer.

Rocker: Since Miller’s passing, his legend seems to grow ever stronger, with concerts commemorating his music, posthumous releases, and this book of course. Do you think that Miller really understood his place in music history? Or had he underestimated himself? Knowing him as you have come to through biographing, what do you think would have been his reaction to the interest in him since his death.

Brett: It was something he seemed to struggle a lot with. He didn’t want to be a pop star, would’ve hated that in fact, but wanted to be known and appreciated on a greater level than he was—a fair thing to ask considering the quality of his work. He was famous for self-deprecation, but I think that covered up a lot of hurt feelings, since he knew how good he was. And that probably ate at him a lot more after the Loud Family’s last tour. The saddest part is that he’d begun to lay groundwork for a new Game Theory album, but had a crisis of confidence and abandoned it. This would be a much happier story if he were getting the same rediscovery behind a new album, and I think that could have happened.

Rocker: In keeping with the title of your book, what made Miller a true pop genius?

Brett: In some ways I would say he was a genius, period—He was computer programming on a fairly high level full time, at the same time he was creating brilliant albums, practically in his spare time. Scott’s ability to conceptualize amazes me: He’d come into an album project with a fully formed idea of how it sounded, the form it would take and how all the pieces fit together. And of course, he wrote songs that embodied some fiendishly complex thought, but were still Beatles-level catchy. He really was that good.

__

Buy “Don’t Thank Me All at Once” at the 125 Records website.

See other titles by Brett Milano at his website.